2015 RE-VISITED, PART TWO: What Makes Legendary Hip-Hop

Dr. Dre and Kendrick Lamar dropped masterpieces this year that made every other hip-hop artist (Drake, Nicki Minaj Future, Meek Mill, Travis $cott, Rae Sremmurd, Fetty Wap, Ty Dolla $ign, Rich Homie Quan etc.) look like a fucking joke.

And that’s no shade on any of the above mentioned rappers. They’re all very talented artists with undoubtedly promising careers ahead of them… but listen: it’s 2015. We have roughly three decades of hip-hop behind us at this point—aren’t we past rapping about how awesome/dangerous/wealthy/sexually proficient/participating in a party featuring alcohol we are? I know I’m making broad generalizations here about the state of modern hip-hop, and I’ll admit I am a sucker for most of the hits these rappers produce. I think Drake creates incredible music that I love and listen to frequently, and he definitely stands miles ahead of his contemporaries in terms of raw talent.

At the same time however, I expect more from the most culturally significant musical genre of the last 20 years; a genre brimming with more artistic and political possibility than any other; an art form responsible for nothing less than giving voice and agency to America’s oppressed.

So when I turn on the radio and hear an auto-tuned drawl that sounds like its owner just rolled out of bed, possibly still drunk and/or high from the night before, singing about how fine a “baby girl” is… well it’s a reality check for my expectations. Drake spent all year asserting his dominance and defending himself from enemies, and yeah Drake, I know you’re arguably the best around right now, I know that you’re a legend and you’re here after you started from the bottom and that’s fantastic, all the power to you and Ima letchu finish Drake…

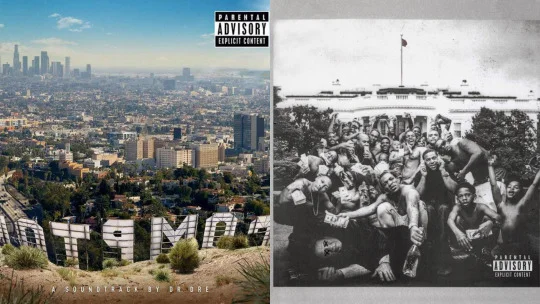

BUT KENDRICK LAMAR AND DR. DRE CREATED TWO OF THE BEST HIP-HOP ALBUMS OF ALL TIME.

Because they aimed for so much higher than money-drugs-cars-women. Because they wasted no time trifling with such baser matters. Because they recognized in hip-hop the potential for evoking poignant, artistic, necessary statements. Because they created complex and poetic music, ambitious in scope and dense in sound. Because they brought together communities to help them create what resulted in beautiful chaos; epic, grand, dynamic, liberated music. Because these albums consistently shift more in tone, mood and timbre over the course of one song than most hip-hop records do in their entirety. Kendrick and Dre invoked concepts, narratives and difficult ideas, all in pursuit of something greater than their genre. Most importantly, To Pimp A Butterfly and Compton challenge the listener, erratically morphing from one musical thought to another in ways that push the limits of their respective artists’ sounds—either forward on the next step of a career’s evolution (Kendrick Lamar), or as a legendary career’s boldly triumphant swan song (Dr. Dre).

To Pimp A Butterfly sounds unlike any other hip-hop album I’ve heard before. It exists on a plane entirely of its own creation. Kendrick reinvented his sound in almost every conceivable way: from the vocal inflections and caricatures of his flow, to the loose and unpredictable jazz-washed production. With his third album, he sought to address a history of racial inequality and systemic oppression against the black American community at a time when it seemed most prevalent and necessary. It is a tremendous, important, instant classic of a hip-hop record. I mean the first song is a fable about Wesley Snipes’ troubled career that samples the title track from the 1974 blaxploitation flick, Every Nigger Is A Star, and features George Clinton—whose genre-busting Parliament Funkadelic served as a huge influence on TPAB—bellowing over Thundercat’s wobbly sci-fi bass tones. Oh and Flying Lotus produced it. And that’s the first track. On “King Kunta” K-Dot brought hip-hop ghostwriting into the conversation months before Meek Mill, indirectly putting Drizzy on notice in a far more tasteful fashion (unless you think hip-hop belongs on Twitter). And he did it withone fucking line in the context of a song with far loftier concerns, in which he invokes archetypal rebellious slave Kunta Kinte in an examination of the legacy of American slavery. Kendrick worked with 70+ collaborators on TPAB, and created an album with more sonic diversity than I think most hip-hop fans are comfortable with, while maintaining its integrity and faithfulness to the genre. It’s definitely not as easy to listen to as good kid, m.A.A.d city; it gets in your face from minute one and never caters to popular expectation. TPAB’s lead single, “i,” released 6 months prior to the album’s release, could’ve been the poppiest, most accessible song on the record… if it sounded anything like the “i” that ended up appearing on the album, in which Kendrick tagged on a spirited spoken word epilogue, and altered his flow and enunciation to sound like the haunting, purple demon Kendrick he unveiled in an undoubtedly game-changing SNL performance of the song:

And that video speaks volumes about what distinguishes Kendrick from his contemporaries, and what aligns him with some of the greatest hip-hop artists of all time: he is constantly and fearlessly pushing the limits of his art, in pursuit of creating something unique, timeless and honest; something we have not heard before.

If Drake is the King of Hip-Hop, then Kendrick Lamar is its Warrior Poet, and he owes him no fealty.

K-Dot appears no less than 4 times on Dr. Dre’s Compton, and somehow manages to shine amongst an incredible roster of hip-hop veterans featured on the album. Compton sounds certainly more vintage and classic than TPAB, but it’s somehow more mercurial and schizophrenic. Each song plays out like a miniature compilation of wildly different beats and melodic refrains, like flipping through a string of hip-hop radio stations. When a new featured rapper appears on a track, it often signifies these shifts in tone and production, and it’s fascinating. From the get-go, Dre makes it clear that Compton is a democratic process, and he’s giving each of his friends a mini-beat of their own to spit over. Take the first minute of “Loose Cannons,” which finds Dre rapping over a relaxed, brassy refrain before Cold 187um jumps in to push the track into manic, menacing territory, complete with orchestral blasts and electric guitar. Xzibit interrupts us at 1:30, and the song shifts yet again to a classic Dre—but still demented—gangsta stomp that takes us all the way to the song’s murderous conclusion. The rest of the album is teeming with similar levels of musical diversity and excess, as if Dre insisted that no collaborator big or small be left out. Singers and rappers alike chirp and bark in random places, little bursts of every conceivable instrument seem to fill in the blanks, and voices get modulated seemingly with capricious abandon. And through it all, Dre holds his own, sounding just as nimble and spry as ever (especially for a 50 year-old), begging the question of why he’s choosing to retire at a time when he seems most fired up. Compton is a celebration and retrospective of all that distinguished him as a hip-hop legend, but Dre’s not going out in anything but a hail of gunfire, and the album sounds remarkably ahead of its time. It’s this synthesis of old and new that separates it from most of the lazy synth-driven beats circulating in most other rap music. “Genocide” pairs a sinister sci-fi engine rev with Candice Pillay’s dancehall chants, but with its jazzy choral refrain (“Stone cold killers in these Compton streets / One hand on the 9, all eyes on me / Murder, murder, it’s murder, it’s murder”) it could sound like anything from 1992 to 2022. Oh and almost every song has a chorus, a real goddamned bonafide chorus with distinct melodies and harmonies like the kind Nate Dogg used to sing. Anderson Paak and Marsha Ambrosious take the reigns on a lot of them, but that doesn’t scratch the surface of how many voices seem pipe in at any given moment throughout the album. Like TPAB, Compton overflows with content, message, talent. Like TPAB, it reaches for the stars. It doesn’t test the waters, it jumps right in without a lifejacket and seeks to sound like no other hip-hop album out there.

And like To Pimp A Butterfly, it succeeds.

There isn’t going to be a serious conclusion to this. Hip-hop is an ecclectic, diverse genre of music, and everyone is entitled to their preference. But I think we can do better.